Reverse Heart Attack Damage

Can heart attack damage be reversed?

In medical school, Gerald Karpman was taught that when it comes to matters of the heart, what’s done is done.

“If you survived the heart attack, you survived at the level that you were going to be,” he recalls. “Whatever damage was done was permanent.”

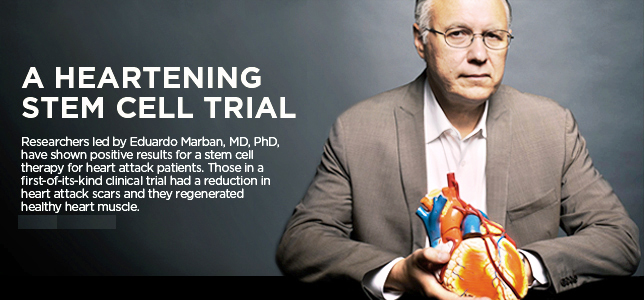

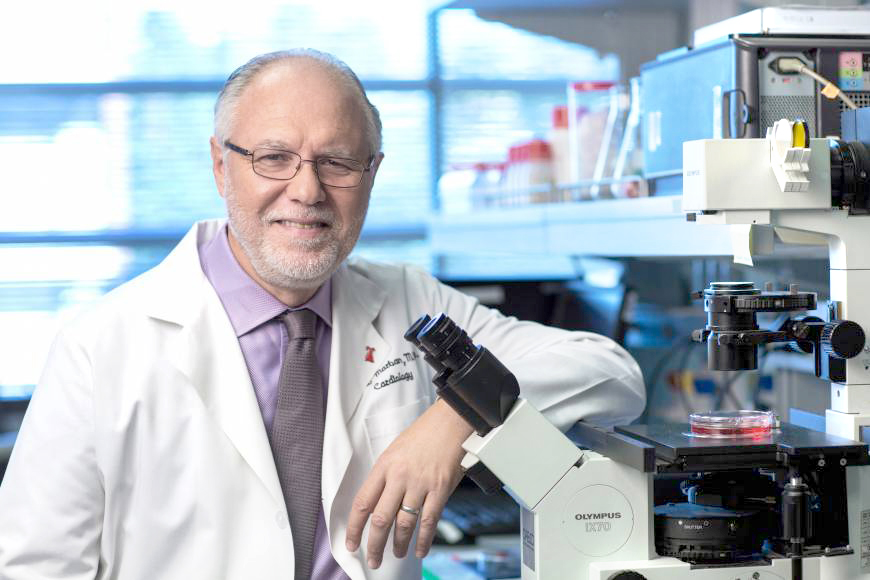

Dr. Eduardo Marban, director of the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute in Los Angeles, and fellow scientists are creating a biological pacemaker, by injecting a gene into the hearts of sick pigs that changed ordinary cardiac cells into a special kind that induce a steady heartbeat. Their study, published Wednesday, is one step toward developing an alternative to electronic pacemakers that are implanted into 300,000 Americans a year. (credit: AP)

That thinking has prevailed until very recently, when studies involving a handful of patients showed an infusion of stem cells might help rebuild healthy hearts in heart attack survivors.

On March 7, Karpman joined that perilous club. A dermatologist in Camarillo, California, and a former marathon runner, the 66-year-old had a rigorous routine: eight to 10 miles of walking each day and a meticulous, meatless diet.

But that morning, sitting at his home computer, a pain kicked in.

“Within about 30 seconds, I was in extreme discomfort,” recalls Karpman, who says it was worse than the kidney stones he once suffered. “I couldn’t sit still. I mean even driving the car (to the hospital), I couldn’t put a seat belt on; I’m just moving around, just trying to think of something else.”

Karpman made it to Los Robles Hospital and Medical Center in Thousand Oaks, where doctors used stents to reopen an artery in his heart and save his life.

As he lay recovering, he took in some grim news: Nearly 20% of his heart muscle was dead, starved of oxygen. Dead heart tissue leaves a scar, interrupting the coordinated muscle action that makes the heart such an efficient pump.

A standard measure of the heart’s pumping ability is the ejection fraction, the percentage of blood in the left ventricle that is pumped out with each heartbeat. A healthy ejection fraction is between 55 and 70, according to the American Heart Association.

Damage as severe as what Karpman suffered carries a high risk of developing heart failure.

An hour’s drive to the southeast, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, Dr. Eduardo Marban has recently launched an experiment to help patients like Karpman.

Marban led one of the earlier stem cell trials, using cells taken by biopsy from the patient’s own heart. The cells were multiplied in a laboratory for two to three weeks and then reinfused through a catheter. At the time, says Marban, it was thought that the stem cells themselves turned into new heart muscle and blood vessels.

“In fact, the more we learned, the more we realized that that’s not what these cells do,” he says. “They can make heart muscles and blood vessels in a dish very nicely. But in the living organism what they seem to do is secrete factors that wake up the surrounding heart muscle.”

Like re-charging a battery, the infusion of new cells seems to trigger the body to produce new tissue: new muscle and blood cells.

“The cells will only be there a few weeks before they’re immunologically rejected, but during that time they do their magic, and their magic stays behind long after the cells are gone,” explains Marban.

Shifting his approach, Marban developed a process that avoids the need for a biopsy, instead using stem cells taken from the hearts of organ donors. Technicians select and grow the strongest cells, which are stored until needed.

Using an off-the-shelf product offers some advantages, Patients undergo one procedure, instead of two. That means it can be administered sooner after a heart attack, which in theory might speed recovery. Also, with the two step-process, some patients’ stem cells were hard to grow in the lab. With Marban’s approach, the patient is assured of getting carefully screened, vigorous cells.

Marban and his collaborators are looking to test the treatment at 25 to 35 hospitals around the United States, on a total of more than 300 patients with moderate or severe heart damage. Since enrollment began earlier this year, a few dozen have received the stem cell infusions. Officially it’s known as the Allogeneic Heart Stem Cells to Achieve Myocardial Regeneration trial, or ALLSTAR.

Nine weeks after his infusion, Karpman is back to walking four miles a day. He’s taking a more relaxed approach to his health, but says he’s regained a lot of strength. What he doesn’t know is whether stem cells get the credit. A third of the ALLSTAR patients receive a dummy treatment — a placebo — and Karpman won’t find out until the study is over which group he falls into.

“It may be the placebo effect; it may be the stem cells,” he says. “I haven’t thought too much about it. I’m just happy that I’m feeling better.”

In a quiet moment, he reflects on what an effective treatment could mean to his profession.

“My dad was a general practitioner. He was old school; he made house calls, I used to go with him in the evening. And he had two books that had all the information he needed to use in medicine. I have bookshelves just on dermatology. The amount of advancements in knowledge is mind-boggling,” says Karpman.

“To have something that actually repairs that damage that was done (from a heart attack), it’s remarkable.”

Source: Caleb Hellerman / CNN