Irresponsible tourism threatens the endangered orangutan’s survival

Mina might be a cantankerous beast, but she’s a sucker for bananas.

When the bananas stop, however, watch out.

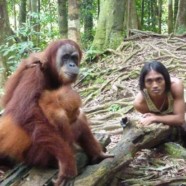

Amid lush jungle greenery, Mina squats on the ground, facing a man who indulges her banana obsession. Her baby plays in a tree nearby. The man calls to a group of tourists, who quickly climb the trail to glimpse what they’ve come for: orangutans.

None of the visitors seems phased that the guide is violating the warning at the park entrance, “Do not feed the orangutans.”

Like many gap-year students from Europe who pass through Bukit Lawang on extended trips around Southeast Asia, they are understandably mesmerized by this close encounter with a wild species amazingly similar to themselves, albeit covered in an abundance of long orange hair.

They start taking pictures. Then two park rangers spot the guide, and tell him off.

The visitors only have time to take a few more pictures before Mina loses interest in the guide, and walks toward them. “Start walking away” warn the park rangers. Mina lumbers worryingly close. “Now run,” they add.

Too late. A strong, hairy hand clasps a trembling knee.

“Stay calm,” one park ranger says, as Mina gradually wraps herself around one of the tourists. Maybe his faintly orangutan-esque facial hair has distracted the animal from a distinctly human outfit: lumberjack shirt and swim shorts.

Mina seems more amorous than aggressive, but the tourist has been warned about this notoriously unpredictable local celebrity. He doesn’t look comfortable in her embrace. After twenty minutes of intense negotiations between Mina and the park rangers, she eventually lets him go, unharmed.

Mina is well-known in this part of Gunung Leuser National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Every guide has a story about her. She interrupts lunches, opens backpacks to search for food, and scares tourists, sometimes hurting them or dragging them to the ground. Experts say she should be removed from the area; she has become too aggressive, dangerous to tourists and by extension, to herself.

Darma, one of the park rangers, blames unscrupulous tour guides. “Some guides bring food to attract orangutans and please tourists. When they prepare lunches, sometimes they pack an extra portion of nasi goreng for Mina,” he says, referring to Indonesia’s popular stir-fried rice dish.

But orangutans are critically endangered.

Tasty as it is, nasi goreng doesn’t offer the same quality of nutrition as their natural diet of fruit and leaves from the forest.

Apart from making orangutans aggressive when they’re deprived of food they shouldn’t have in the first place, the main risk of feeding and touching orangutans is contamination. Although they remind us so much of ourselves — their name in Indonesian literally means “forest person” — they have no immunity to human diseases, explains Panut Hadisiswoyo, director of the Orangutan Information Center, a local NGO.

Like their cousins in Borneo, the population of Sumatran orangutans is drastically declining, due to poaching and above all the destruction of their natural habitat. Their last stronghold is the 3,000-square-mile Gunung Leuser National Park, adjacent to Bukit Lawang, on the border between North Sumatra and Aceh provinces.

All around the park, mines, logging sites and palm oil plantations have wiped out vast tracts of Indonesian rainforest. The WWF, or World Wildlife Fund, estimates the number of remaining Sumatran orangutans at 7,500 individuals, and believes that the population may decline by 50 percent in a decade — and by 97 percent in 50 years if habitat loss continues.

The Bohorok Orangutan Center opened in Bukit Lawang in the ’70s as a rehabilitation center to reintroduce captive orangutans to the wild. More than 200 were brought to the area, rescued after having been poached from the wild. As the first visitors started showing interest, attracted by the possibility of getting close to the apes, the WWF expressed concerns that an increasing number of tourists could put the orangutans at risk of contracting human diseases.

The rehabilitation center has since closed, but tourists haven’t stopped coming. Guesthouses line up along the Bohorok River and new ones are under constructions in the few empty spaces, to accommodate more than 10,000 people who visit every year.

A legacy of the rehabilitation center, feeding platforms remain, and semi-wild orangutans visit them twice a day for the only officially sanctioned feeding in the park, giving visitors an incredible close-up experience with the beautiful creatures.

But conservation experts say the feedings are more effective in attracting tourists than in reintegrating orangutans into the wild. Given that nearly all the orangutans in Gunung Leuser were either born in the forest or have lived there at least since the rehabilitation center closed 20 years ago, they should not require feeding by humans at all.

The mortality rate is much higher in the area than it is in the wild, which is also the case in the very popular rehabilitation center in Sabah, Malaysia, according to Panut Hadisiswoyo. That indicates “that tourism might have a negative impact on orangutans’ survival.”

Experts believe that high infant mortality rates may be a result of diseases and poor motherhood skills due to contact with humans. Darma has no doubt that human contact has an effect. “We have one orangutan here, who had seven babies, including five who died.” He jokes, “But of course, she’s posing … for calendars, she’s too busy to be a good mum!”

“Regulating tourism is the only way for long term survival of orangutans in the area,” says Panut Hadisiswoyo, adding there shouldn’t be more than 50 visitors allowed in the area per day. While the yearly average is relatively low, in the holiday season the park can be swamped by several hundred tourists all entering at the same time.

To him, if opening the area to tourists was a “mistake,” in terms of orangutans’ well-being, it had some paradoxically positive effects.

“Tourism means the area has become highly protected. Local people protect the forest,” he says. If tourism is well managed and regulations and guidelines are enforced, he adds, Bukit Lawang can also be a powerful tool to educate and alert the public about the fate of Sumatran orangutans.

“It was a mistake to mix reintroduction of orangutans with tourism but we can’t stop it. What we can do now is manage the tourism and promote low impact tourism on orangutans’ natural habitat.”

There are a number of guides and rangers dedicated to improving things, and a growing number of tourists seeking them out. A bit of internet research on travel forums will uncover plenty of information on finding reliable, responsible guides.

But experts recognize that consumer preferences will always hold sway. Until a majority of visitors want to experience the forest in something approaching its natural state, rather than a circus in the jungle with Mina as its chief attraction, little will change.