Spesies Baru Ikan Listrik

Ilmuwan Temukan Spesies Baru Ikan Listrik

Daya listrik yang dikeluarkan oleh ikan yang baru ditemukan itu tidak dapat dideteksi oleh manusia.

Para ilmuwan mengatakan mereka telah menemukan sebuah genus dan spesies baru ikan pisau elektrik di Sungai Negro, Brazil.

Procerusternarchus pixuna, the new species collected in shallow tributaries of the upper Negro river, a tributary of in Amazon River in Brazil.

Procerusternarchus pixuna adalah ikan kecil, berukuran antara 75 mm sampai 138 mm, dan voltase atau day listrik yang mereka keluarkan sangat kecil sehingga diukur dengan mikrovolt, yang berarti bahwa manusia tidak dapat mendeteksi aliran listrik tersebut.

Sebagai perbandingan, belut listrik, yang ada di ordo spesies sama dapat mengeluarkan aliran listrik sampai 600 volt.

Seperti ikan lain dalam genus ini, Procerusternarchus pixuna menggunakan daya listriknya terutama untuk menemukan ikan lain.

Menurut Profesor Cristina Cox Fernandes dari University of Massachusetts di Amherst, salah satu penulis makalah yang menggambarkan Procerusternarchus pixuna, ikan itu tidak berenang secara bergerombolan. Bahkan mereka saling menjauh untuk menghindari saling mengaliri listrik. Ia menambahkan bahwa ikan jantan dan betina dapat mengubah kekuatan aliran listrik jadi tidak saling menyengat.

Hanya dua dekade lalu, ada kurang dari 100 spesies ikan listrik yang terdokumentasikan, namun jumlah itu naik hampir dua kali lipat, menurut para ilmuwan.

==================================================

New Electric Fish Genus and Species Discovered in Brazil’s Rio Negro

UMass Amherst fish biologist and colleagues describe new electric knifefish

AMHERST, Mass. – Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA), Brazil, this week report that they have discovered a new genus and species of electric knifefish in several tributaries of the Negro River in the Amazonia State of Brazil.

Professor Cristina Cox Fernandes at UMass Amherst, with Adília Nogueira and José Antônio Alves-Gomes of INPA, describe the new bluntnose knifefish in the current issue of the journal Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

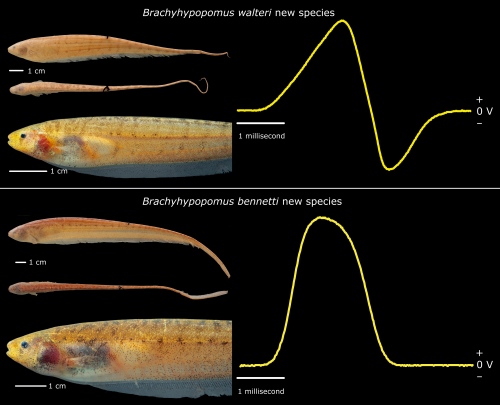

Their paper offers details about the new genus and species’ anatomy, range, relationship to other fish, salient features of its skeleton, coloration, electric organs and patterns of electric organ discharge (EOD). True to their name, these fish produce electric discharges in distinct pulses that can be detected by some other fish.

Cox Fernandes says the discovery of this species is leading to a new interpretation of classifications and interrelationships among closely related groups. She adds that as the diversity of electric fishes becomes more thoroughly documented, researchers will be able to explore possible causes of this group’s adaptive radiation over evolutionary time.

Last year, with colleagues including ichthyologist John Lundberg at the Academy of Science in Philadelphia and others at Cornell University and INPA, the UMass Amherst fish biologist co-authored a description of three other electric fishes. The authors provided details about the most abundant species of apteronotid, so-called “ghost knife fishes,” another family of electric fish very common in the Amazon River and its large tributaries.

In the early 1990s, Cox Fernandes recalls, when she began her studies of the communities and diversity of electric fishes, fewer than 100 species were then scientifically described. But with the current journal article and studies by herself and others, the number has roughly doubled today. Electric fishes are of little commercial importance, but in her opinion fishes of the Neotropics, especially in the Amazon, are still “under studied,” and more taxonomic studies such as the one are needed.

She adds, “As environmental changes affect rivers worldwide and in the Amazon region, freshwater fauna are under many different pressures. Fish populations are dwindling due to the pollution, climate change, the construction of hydroelectric plants and other factors that result in habitat loss and modification. As such the need to document the current fish fauna has become all the more pressing.”

source: Cristina Cox Fernandes / www.umass.edu